MISSISSIPPI'S MOSES

MCCOMB, MS — SUMMER 1961 — Freedom Riders were coming South. Martin Luther King was marching and making headlines. But Mississippi was “the closed society” ruled by the Klan, Jim Crow, and raw fear. Then that sizzling August, a lone black man came to Amite County in the deep, Deep South. With no fanfare or speeches, he began leading a few “Negroes” to the courthouse. Their goal was simple — register to vote.

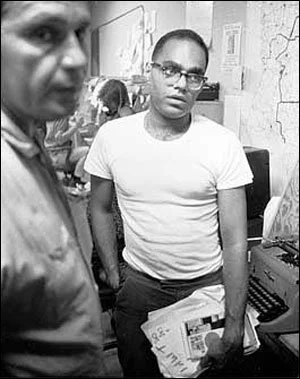

Arrested, beaten bloody, the man startled cops with his calm. In police custody, given one phone call, he called the Justice Department in Washington, D.C., collect, to “report civil rights violations in Amite County.” Jailed, he refused bail. Finally released, he was escorted out by hulking sheriffs. “Boy,” one asked him. “Are you sure you know what you’re about?”

After MLK, Bob Moses was the most influential civil rights leader. If you never heard of him, it’s because he wanted it that way. Freedom, he had learned from Ella Baker and her Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, did not come from stirring speeches. Freedom came by stirring people, from the ground up.

And few were better at stirring people than Bob Moses. “We were immensely suspicious of him,” Julian Bond said of first meeting the quiet, cerebral Moses in King’s Atlanta office. “We had tunnel vision. Bob Moses, on the other hand, had already begun to project a systematic analysis; not just of the South, but of the country, the world.”

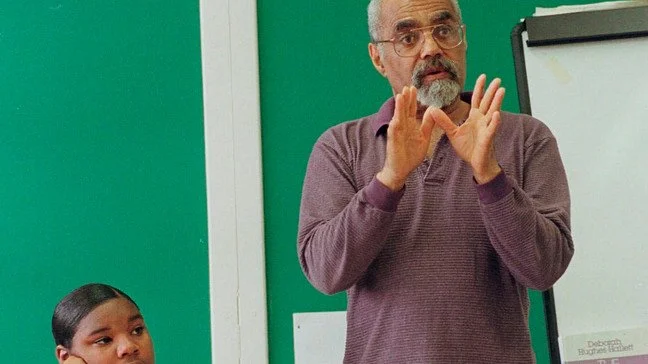

I met Bob Moses in 1994, when writing about his Algebra Project. He came slowly across a Brooklyn classroom, gave me a limp handshake, and in a voice as soft as silk, said, “Hello, I’m Bob.” No hint of ego, of accomplishment. Only later, when driving with him through the Mississippi Delta, as he pointed out a site where “one of our cars went off the road,” a town “too dangerous to organize,” did I learn the full story.

The son of a Harlem janitor, Moses rose on sheer intellect from high school to Harvard. His favorite author: Camus. His favorite subject: math. But after earning a Master’s in philosophy at Harvard, he left to care for his ailing father. Drawn into the Civil Rights movement, he gave up a cushy private school teaching job to work with King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

In the summer of 1961, when King needed someone to start an office in Mississippi, Moses volunteered. He paid his own bus fare and went there — alone. The rest is as much legend as history, culminating sixty years ago in Freedom Summer.

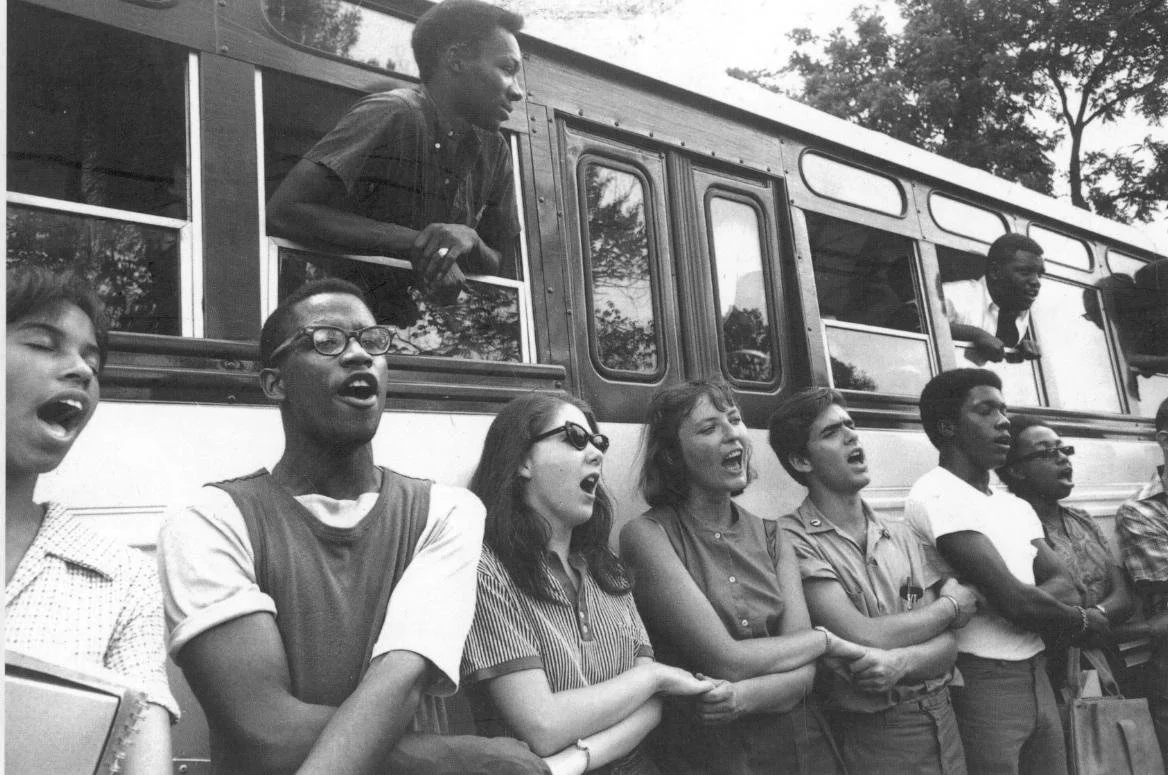

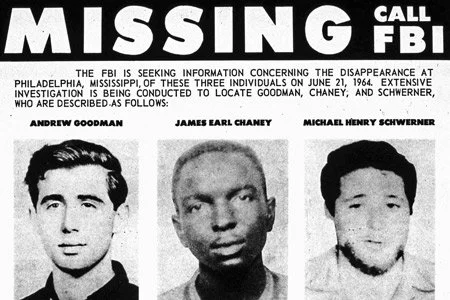

During the summer of 1964, 700 college students came to Mississippi to work on voting drives, teach in Freedom Schools, and just be in Mississippi, living with “black folk.” On the first day of that fabled summer, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Mickey Schwerner disappeared. Their bodies were found weeks later, buried beneath an earthen dam. The story usually ends there, but the story runs much deeper. And like grassroots, it grows from seeds, seeds planted by Bob Moses.

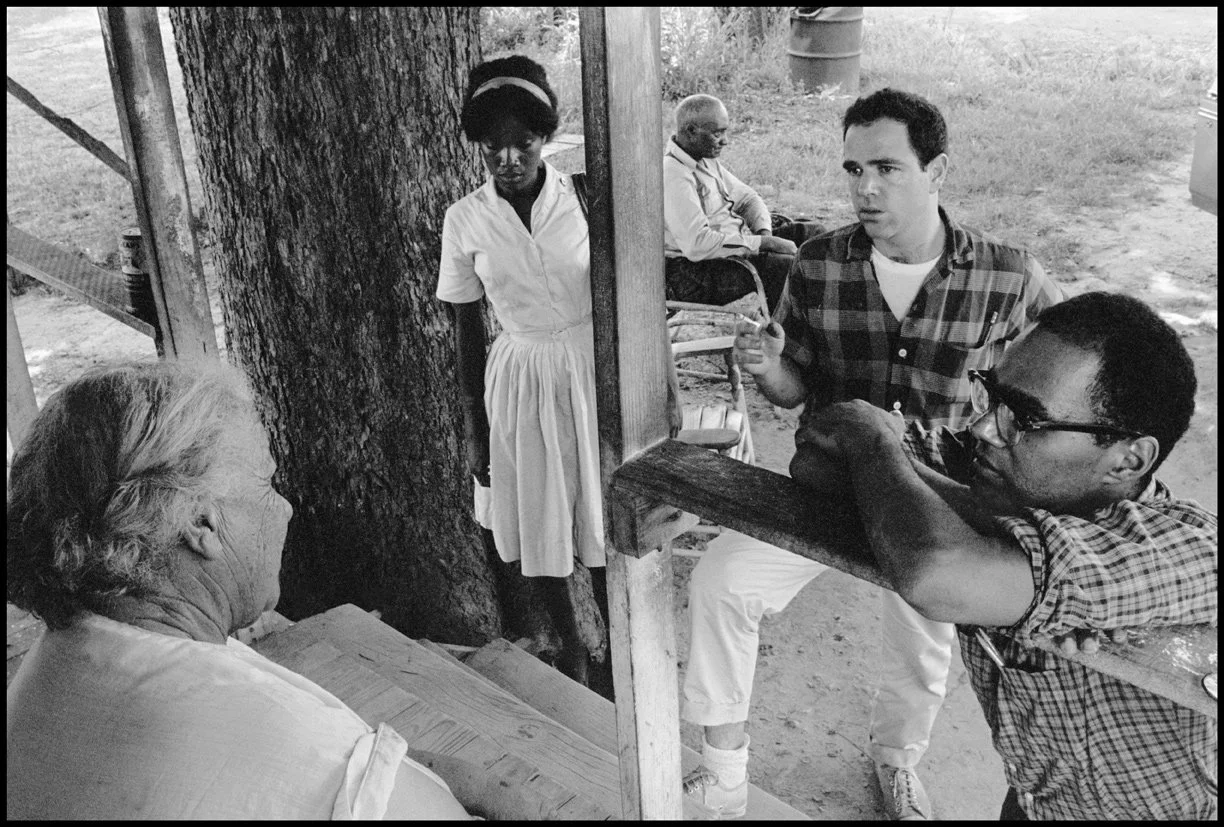

Before Freedom Summer, Moses spent three years in Mississippi. First in Amite County, then in the cotton capital of Greenwood, he organized a movement — person by person. Voting was the key to opening “the closed society,” so he and his recruits reached out to sharecroppers and barbers, maids and cooks, finding the few who could overcome the terror of night raids and burning crosses, getting them to lead each other to courthouses.

By 1963, when Medgar Evers was gunned down, Moses saw that “it’s not working.” America at large, wary of King, weary of “the Negro problem,” cared nothing about Mississippi. To make them care, Moses brought the sons and daughters of America to Mississippi.

Stories of Freedom Summer tell of courage, hope, and endurance. They usually mention Bob Moses as mastermind behind the scenes, but he was all over Mississippi that summer. Visiting Freedom Schools (featured next week in The Attic), organizing Mississippi Freedom Democrats, negotiating, teaching, and just being Bob Moses, a beacon of courage.

Stories circulated among volunteers. How Moses had come into a SNCC office after it was bombed, laid out a cot and took a nap. How when riding through the Delta, a shotgun blast hit the driver, forcing Moses to grab the wheel. How he sat in an all-white courtroom and pressed charges. . .

When he first came to Mississippi, it was, the NAACP chair said, “the bottom of the barrel.” Just seven percent of blacks could vote. When he left four years later, the “closed society” teemed with marchers, registration drives, and Freedom Schools. And 60 percent of blacks could vote. Bot Moses, however, was burnt out.

He spent a decade in Africa, teaching, raising a family. Returning to America, he was one of the first MacArthur geniuses. He used his grant money to do what he left behind when he came South — teach math. For the rest of his life, Moses ran The Algebra Project, blending Civil Rights history with innovative math games to get inner city kids excited about algebra.

No one would have bet on Bob Moses to survive Mississippi, but he died in 2021 during the George Floyd protests. “I certainly don’t know, at this moment, which way the country might flip,” Moses told the New York Times. “It can lurch backward as quickly as it can lurch forward.”

There was no great funeral, no national mourning. But across Mississippi, thousands of Freedom School graduates, working in law or politics or education, gave thanks. Meanwhile, hundreds of Freedom Summer volunteers reflected on their brush with greatness.

In the summer of 1961, Moses wrote a letter from jail. “This is Mississippi, the middle of the iceberg.” His letter went on to describe his cellmates singing, practicing SNCC’s “jail with no bail.” “This is a tremor from the middle of the iceberg, from a stone that the builders rejected.”