THE JEWEL OF THE SUMMER -- FREEDOM SCHOOLS

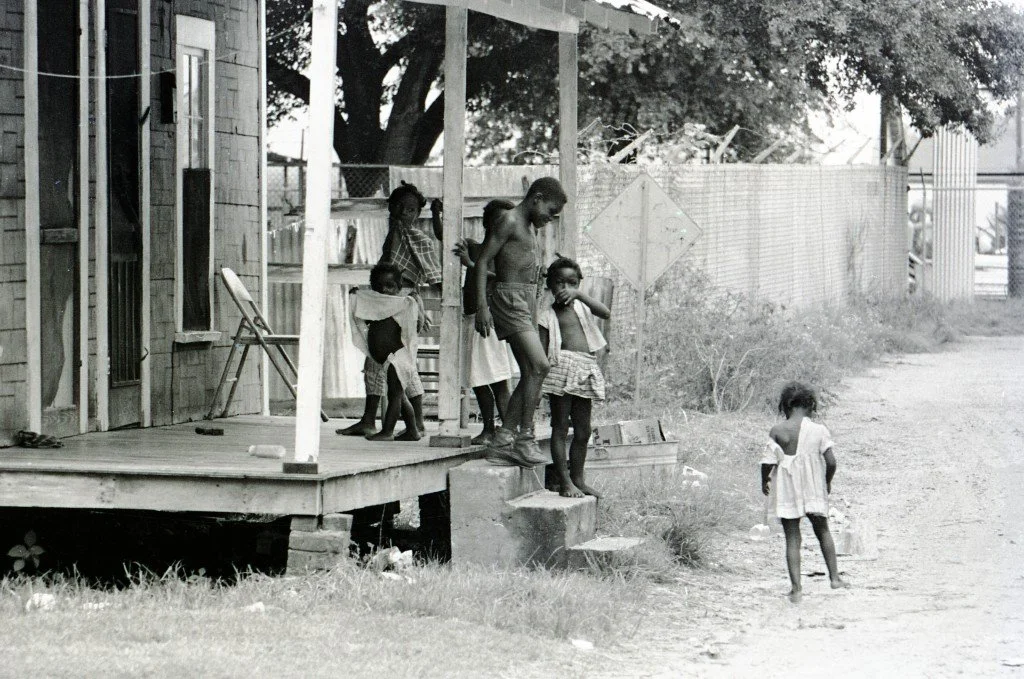

RULEVILLE, MS, JULY 1964 — School is out. Cottonfields bake beneath the cruel sun. With fewer black hands needed before cotton’s “lay-by” time, this Delta town sleeps. Until. . .

At 8:00 a.m. kids begin clamoring outside a small shed on the edge of the cottonfields. The teacher is coming! Class is about to begin! But not another deadly day of dull lessons in a classroom crammed with 50 kids. This is a different kind of school. A Freedom School.

Sixty summers ago, a bold experiment in education filled the sheds and shacks of rural Mississippi. The Freedom Schools, though planned as a mere adjunct of Freedom Summer, were that summer’s jewel.

Not enough blacks registered to vote that summer. Come August, the Mississippi Freedom Democrats were turned away from the Democratic Convention But Freedom Schools burst at the seams with learning, love, and what Bob Moses called “radical equations.”

“Freedom School” sounds like an oxymoron, but not when compared to Mississippi’s “separate but equal” schools. In a state where just 7 percent of blacks graduated from high school, per pupil expenditures for white students were five-to-fifty times the amount spent on black students. Heroic black teachers toiled in rotting classrooms with ancient texts, no equipment, and only the most basic subjects.

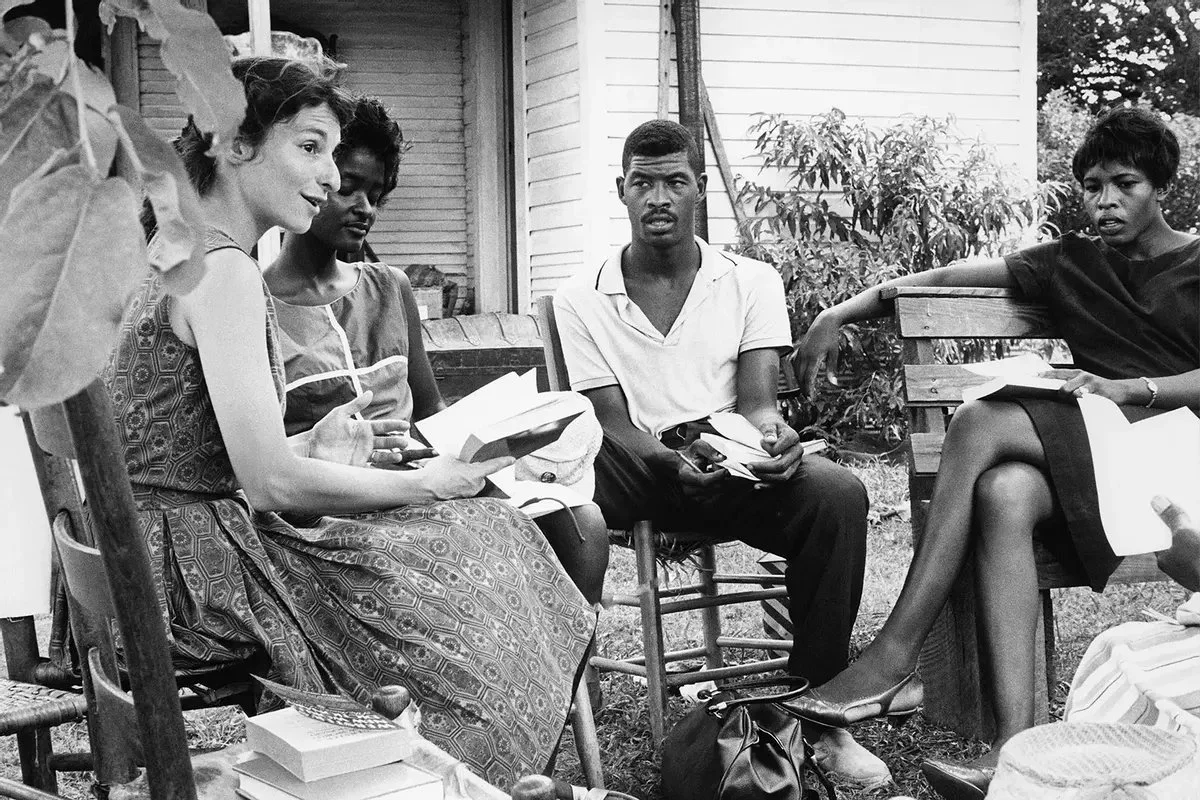

“This is the situation,” Freedom Summer recruits read in SNCC’s Notes on Teaching in Mississippi. “You will be teaching young people who have lived in Mississippi all their lives. That means that they have been deprived of decent education from first grade through high school. It means that they have been denied free expression and free thought. Most of all it means that they have been denied the right to question. The purpose of the Freedom Schools is to help them begin to question.”

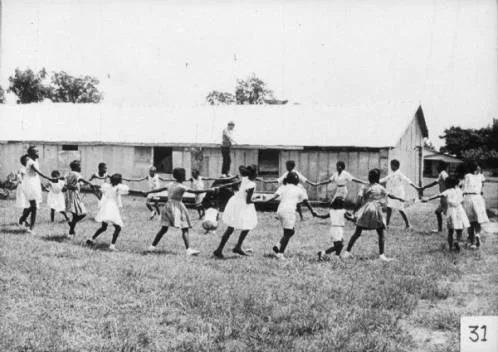

Coming into Mississippi from across America, teachers spent the first week of July preparing. Prep involved everything from building a bookcase out of boards from an old outhouse to cleaning out ancient shacks and setting up crude benches. Some 1,000 students were expected. After all, it was summer. School? Freedom in school? But on July 8, 1964, as the South chafed against the landmark Civil Rights Bill signed that week, 2,000 students showed up. Many were adults, asking only to be taught to read.

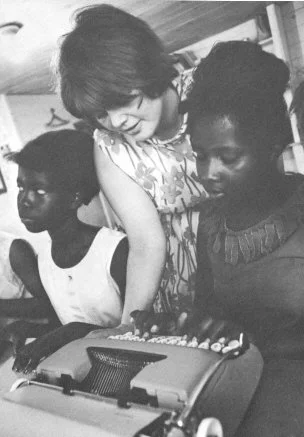

Teachers, most teaching their first classes ever, threw their souls into their work. “Be creative,” SNCC’s teaching guide told them. “Experiment. The kids will love it.” Along with reading, writing, and ‘rithmetic, Freedom Schools taught subjects no black school could touch. "Neither foreign languages nor civics shall be taught in Negro schools,” white school boards decreed. “Nor shall American history from 1860 to 1875 be taught."

But in Freedom School, students were asked to consider. Why did white folks have so much and black folk so little? Have you heard about Dred Scott? About the Middle Passage? Stories of the Amistad slave rebellion spread smiles across black faces. Students fell in love with Langston Hughes, reading his poems aloud. One student remembered reading Richard Wright’s Black Boy in the Greenwood Freedom School. “I kept thinking, ‘Well, you mean black folk can actually write books?’ Because I’d always been told blacks had done no great things, they hadn’t done anything, we had nothing that we could be proud of.”

Greeted each morning by kids rushing to take their hands, teachers were overwhelmed. “Dear Mom and Dad,” one wrote home. “The atmosphere in class is unbelievable. It is what every teacher dreams about — real, honest enthusiasm and desire to learn anything and everything. The girls come to class of their own free will. They respond to everything that is said. They are excited about learning. They drain me of everything that I have to offer so that I go home at night completely exhausted but very happy.“

As summer went on, curriculum expanded. Some schools taught typing. One added a French class. And most published mimeographed newspapers — The Ruleville Freedom Fighter, The Shaw Freedom Flame — with student poetry, essays, and line drawings.

Teachers taught till noon, broke for lunch, ran afternoon sessions, went home for dinner, and returned for evening work with adults. Trained to expect low pay, they worked for no pay. Their ten-dollar weekly room and board came out of pocket.

But by mid-August, students sensed the end of Freedom School. Cotton would soon demand picking, and regular, boring school loomed. Students, one teacher wrote, “are beginning to realize that we’re not saviors and we’re not staying forever and we’re not leaving any miracles behind.”

In late August, Freedom Schools closed, but not for good. Dozens re-opened the following summer, some staffed by returning teachers. As summer followed summer, however, fewer Freedom Schools stayed alive. The experiment, pulled off at an expense of $2,000 in 1964, could not be sustained forever. The torch, however, had been lit.

No one knows how many Freedom School alumni went on to high school, college, and careers, but the schools have been widely studied and emulated. Local Freedom Schools can be found today in several cities. Since 1995, the Children’s Defense Fund, founded by Marian Wright Edelman who represented Freedom Summer volunteers in court, has seen its Freedom School program grow from two sites to more than 100 serving 11,000 students.

“We’re giving these kids a start,” one teacher wrote home in 1964. “They’ll never be the same again. This isn’t something anyone can just snap off when the summer ends.”