SPEAKING TRUTH TO TEXAS

AUSTIN, TX, MAY 24, 1982 — With the rap of a gavel and the doffing of cowboy hats, the Texas State Legislature is called to order. Tomorrow’s Austin American-Statesman will dryly note which bills were passed. And the Texas Observer will write:

“The most amazing, amusing and fascinating of games once again bursts upon us in all its insanity. The stakes they play for in politics are paper and money. The chips they play with are your life.”

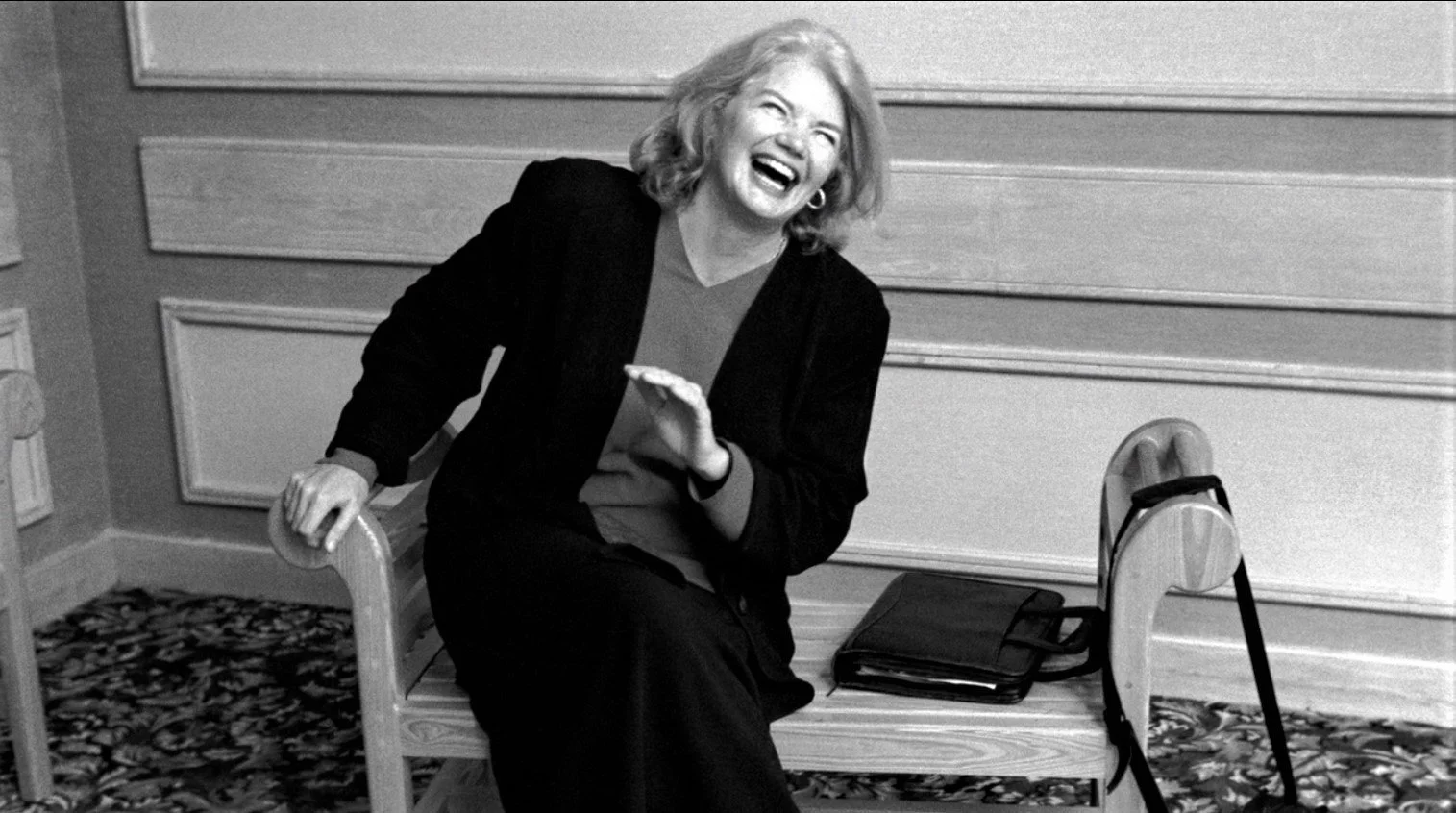

Molly Ivins was a throwback to the days when reporters drank hard, wrote rough, and did not let “facts” stop them from speaking truth to power. To wit:

“I am not anti-gun. I'm pro-knife. Consider the merits of the knife. In the first place, you have to catch up with someone in order to stab him. . . Plus, knives don't ricochet. And people are seldom killed while cleaning their knives.”

Ivins was not on the political beat long before editors recognized her genius for the quip, the comment, and the truth. At the Dallas Times-Herald, she shocked the powers that be, leading the paper to put up bulletin boards reading “Molly Ivins Can’t Say That, Can She?” Later, at the New York Times, she shocked editors by wearing gaudy dresses, swearing, and walking barefoot around the newsroom.

But wherever she worked, Ivins had favorite targets — ignorance, arrogance, and the intoxication of men under their influence. “I’ve always had trouble with male authority figures,” Ivins says, “because my father was such a martinet.”

James Ivins, aka “General Jim,” was on oil company executive and staunch Republican. Molly, growing up in a posh Houston neighborhood, fought with her father nightly. Young girls in Texas were supposed to “get married and have six children along the way with the greatest of ease.” But Molly rebelled at an early age.

By sixth grade, she stood six feet tall. “I felt like a Saint Bernard with a bunch of greyhounds.” Excluded from “the norms of Southern womanhood,” she began to think for herself. In Texas, that meant becoming (gasp!) a liberal.

“I believe all Southern liberals come from the same starting point -- race. Once you figure out they are lying to you about race, you start to question everything.”

In 1968, Ivins became the first female police reporter on the Minneapolis Star-Tribune. But her heart was still in Texas.

“Home is where you understand the sons of bitches.”

Except for six years at the Times, Ivins spent her career covering the Lone Star State. First she roamed its vastness, packing a typewriter and one wrinkled dress, sleeping on cots and writing about a place where “art is paintings of bluebonnets and broncos, done on velvet. Music is mariachis, blues and country. . . And shit is a three syllable word with a ‘y’ in it.”

Then in 1982, Ivins got her dream job — columnist. For the next 25 years, she held forth on any and every topic that annoyed or amused her. Twice nominated for a Pulitzer, she earned a few close friends, an array of enemies, and finally, fame.

Ivins’ 1991 collection of columns was a huge best-seller. Suddenly she was everywhere — on NPR and PBS, writing for Mother Jones, The Nation and 400 newspapers in syndication. Fame was hard to slug down.

“I have always been a left-winger and an outsider. I was perfectly cheerful with that role. Then suddenly you’re one of the talking heads on ‘Nightline,’ and you think you must have sold out.”

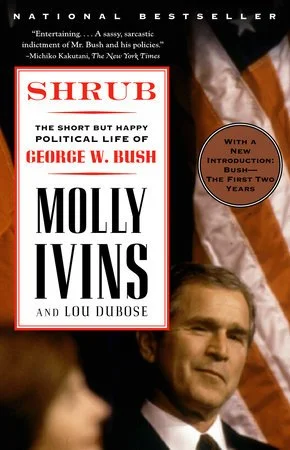

But Ivins never backed down from a fight, particularly against politicians. On Bill Clinton: “He’s as weak as bus-stop chili.” On a Dallas Congressman: “If his IQ slips any lower we’ll have to water him twice a day.” And she took special glee writing about George W. Bush, whom she nicknamed “Shrub.”

“Calling George Bush shallow is like calling a dwarf short.”

But if brevity is the soul of wit, then sorrow is its heart. Behind Ivins’ acerbic tongue was an ache she rarely spoke of. “The love of her life” was a Yale student she met while studying at Smith College. After just a year together, Hank Holland was killed in a motorcycle accident. The tragedy left Ivins “a left-wing, aging-Bohemian journalist, who never made a shrewd career move, never dressed for success, never got married, and isn’t even a lesbian, which at least would be interesting.”

But like many a critic, Ivins’s tough talk grew out of her deep love of politics and the American ideals it is supposed to defend.

“Politics is not about those people in Washington, those people in your state capitol. We run this country, we are the board of directors, we own it. They are just the people we’ve hired to drive the bus for a while.”

Politicians could never silence her, but cancer did. Contracting breast cancer in 1999, she battled for seven years before it claimed her in 2007. She was 62. She is much missed, yet today’s politics might have been hard for even Molly Ivins to laugh at. She certainly saw the writing on the wall.

“When politicians start talking about large groups of their fellow Americans as 'enemies,' it's time for a quiet stir of alertness. Polarizing people is a good way to win an election, and also a good way to wreck a country.”

The Texas State Legislature still “bursts upon us in all its insanity,” but lest the “sons of bitches” get us down, keep Molly Ivins in mind:

“So keep fightin' for freedom and justice, Beloveds, but don't you forget to have fun doin' it. Lord, let your laughter ring forth. Be outrageous, ridicule the fraidy-cats, rejoice in all the oddities that freedom can produce. And when you get through kickin' ass and celebratin' the sheer joy of a good fight, be sure to tell those who come after how much fun it was."