GRACIE FOR PRESIDENT

AMERICA’S LIVING ROOMS — FEB. 28, 1940 — War in Europe. The Depression dragging on. Unemployment — 15 percent. With another election set for November, FDR is pondering a third term. But that night, on radios across the country, a fresh and familiar face announces her candidacy.

“Gracie, coming down to the studio tonight, I saw a big banner saying ‘Vote for Gracie!’ All over town I see billboards saying ‘Put Gracie in the White House!’ What does all this mean?”

“Well, George, I’ll let you in on a secret. I’m running for president.” (Applause)

“You’re running for president? Gracie, how long as this been going on?”

“About 150 years. George Washington started it.”

“Gracie, the idea is preposterous. In the entire history of the United States, there’s never been a woman president.”

“I know. Isn’t that exciting? I’ll be the first one!”

Back in the 1920s, when they met and married, Gracie Allen was the straight man, George Burns the comic. But, George recalled, “I didn't have to be a genius to understand that there was something wrong with a comedy act when the straight lines got more laughs than the punch lines,” So they switched roles. And soared.

“The mating of George Burns with Gracie Allen,” one critic wrote, “almost leads one to believe some marriages are made in heaven.”

Long before Seinfeld, “Burns and Allen” was “a show about nothing.” Playing themselves, they spun humor out of Gracie’s “illogical logic.”

GEORGE: Gracie, where did you get those flowers?

GRACIE: Oh, I got them from Blanche at the hospital.

GEORGE: Really?

GRACIE: Yes, when I was going to visit her, you told me to take her flowers. So when she wasn’t looking, I did.

Delightfully daffy yet a master of wordplay and wit, Gracie charmed America just as she charmed George. But president? As Gracie told it. . .

She was sitting at home with their two children when she looked up and said, “You know, I’m tired of knitting this sweater. I think I’ll run for president.”

Burns and Allen ran with the campaign. The fun started with their half-hour show “Gracie for President.” After naming her political party — the Surprise Party — Gracie chooses a mascot — a kangaroo with a joey in her pouch — and a slogan — “it’s in the bag.” Soon she is promising to resolve the border dispute between Florida and California. After a commercial, reporters show up.

“Miss Allen, my city editor wants to know what’s your opinion on capitalism vs. the little man.”

“Well, I don’t know. I never go to wrestling matches.”

“Are you in favor of monopolies?”

“Well, I don’t play Monopoly. I prefer Mahjong.”

“Gracie,” George finally says. “Why don’t you call this off? You know nothing about it. You haven’t said one thing that’s right.”

“Well, I’d rather be president than right.”

The couple thought they might get one more show out of the gag, but a weary America was eager to laugh. Gracie was soon dropping in on Jack Benny, Eddie Cantor, and the Texaco Radio Hour to take questions.

A female president?

“The Constitution doesn’t say anything about ‘he’ or ‘him’; it refers only to ‘the person to be voted for.’ and if women aren’t persons, what goes on here?”

But presidents are born, not made. . .

“It’s silly to think that Presidents are born, because very few people are 35 years old at birth, and those who are won’t admit it.”

In March, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt invited Gracie to speak to the Women’s National Press Club in D.C. Touting a new campaign slogan — “Down with Common Sense” — Gracie fielded more questions.

What did she think of the Lend-Lease Bill?

“If we owe it, we should pay it.”

With what party was she affiliated?

"I may take a drink now and then, but I never get affiliated."

A campaign bio soon promised “a president in every crackpot.” Gracie was endorsed by the student body of Harvard. After April’s Wisconsin primary, when a Milwaukee newspaper announced her sixty-three write-in votes, Gracie claimed she’d won Wisconsin.

Won? George asks. With sixty-three votes?.

“Oh, that was in only one copy of the paper,” Gracie said. “And that paper has a circulation of 187,000. So 187,000 times 63. . ." Closing the show, Gracie adds, “And when I'm in Washington, don't forget to drop in and see me at the White House. I don't know the address, but I'll leave a Congressman burning in the window."

In mid-April, Gracie and George set out on a whistle-stop tour. In 32 cities, Gracie drew thousands to hear her speak. Bands played. Balloons flew. Gracie kissed baby girls, but insisted that boys wait until they were 21 to be kissed.

Arriving in Omaha, Gracie lit up the Surprise Party convention. A crowd of 8,000 gathered to hear her acceptance speech. The nation tuned in live on NBC. And then, having had all the fun possible, Gracie stepped down. The country faced serious issues, she said. She would let real politicians handle them.

That November, FDR won a third term, carrying all but ten states. Gracie Allen earned a few thousand write-ins. She had made her point. Even in tough times, politics does not have to be so damned serious.

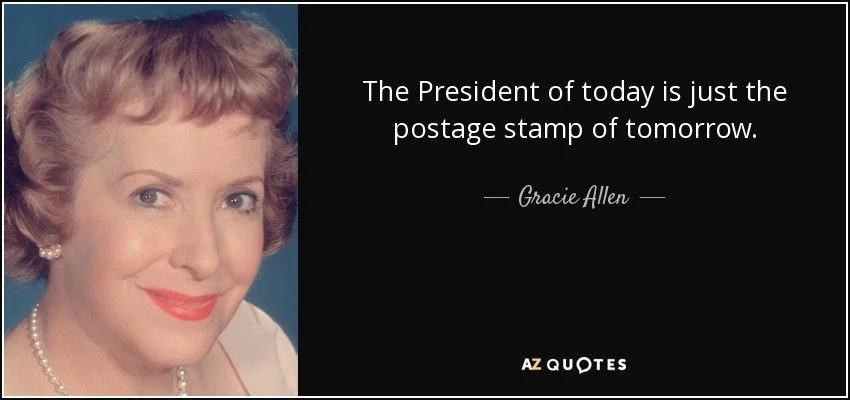

Burns and Allen went on to top radio — then TV ratings. Gracie retired in 1958 and died in 1964, just four years before Pat Paulsen waged his own mock campaign for the White House. But along with her “illogical logic,” Gracie left us with some wisdom for this year.

“I’ll make a prediction with my eyes open: that a woman can and will be elected if she is qualified and gets enough votes.”