"THE GIFT" AND AMERICAN GIVING

HATTIESBURG, MS, JUNE 1995 — Stephanie Bullock was college bound. With all the grit and drive of her mother, whom segregation had kept out of college, Stephanie was senior class president, top student, eager to enter Hattiesburg’s University of Southern Mississippi. But Stephanie had a twin brother and the family couldn’t afford to send both to college. Then one of our “better angels” entered.

When Stephanie won the first Osceola McCarty Scholarship, her grandmother decided to visit the woman who made the dream possible. “I thought she would be some little old rich lady with a fine car and a fine house and clothes.” Instead, the grandmother found herself face-to-face with an 87-year-old black woman in a one-room house. With hands crippled by a lifetime of washing clothes.

A common narrative describes America the Greedy — the big egos, the big bucks, the McMansions and monetized metaphors. Bottom line. . . Bull market. . . Greed is good. . . But a bigger reason explains why Osceola McCarty remains the poster woman of philanthropy.

She was born in rural Mississippi in 1908, the darkest days of Jim Crow. She dropped out of sixth grade to help the aunt who was raising her. She began washing clothes and stashing leftover nickels and dimes in her doll’s buggy. . .

America the Greedy loves such stories. Call them not rags-to-riches but rags-to-rags. The poor folk who, unfazed by cruel fate, labor with dignity. The factory worker who puts four kids through college. Feel better now? Yet there is more to such stories than grateful greed.

Osceola McCarty stood five feet tall and weighed less than 100 pounds. She never married, never had kids, traveled just once outside Mississippi — to Niagara Falls. “The sound of the water was like the sound of the world comin’ to an end,” she remembered. Heading back to Mississippi, she stopped in Chicago. “I liked it, but was ready to get back home.”

McCarty once described her day: “I would go outside and start a fire under my wash pot. Then I would soak, wash, and boil a bundle of clothes. Then I would rub ’em, wrench ’em, rub ’em again, starch ’em, and hang ’em on the line. I’d wash all day, and in the evenin’ I’d iron until 11:00. I loved the work. The bright fire. Wrenching the wet, clean cloth. White shirts shinin’ on the line.”

By the mid-1980s, clerks at the Trustmark National Bank noticed something unusual about the diminutive washerwoman who made small weekly deposits. Her savings account topped $200,000.

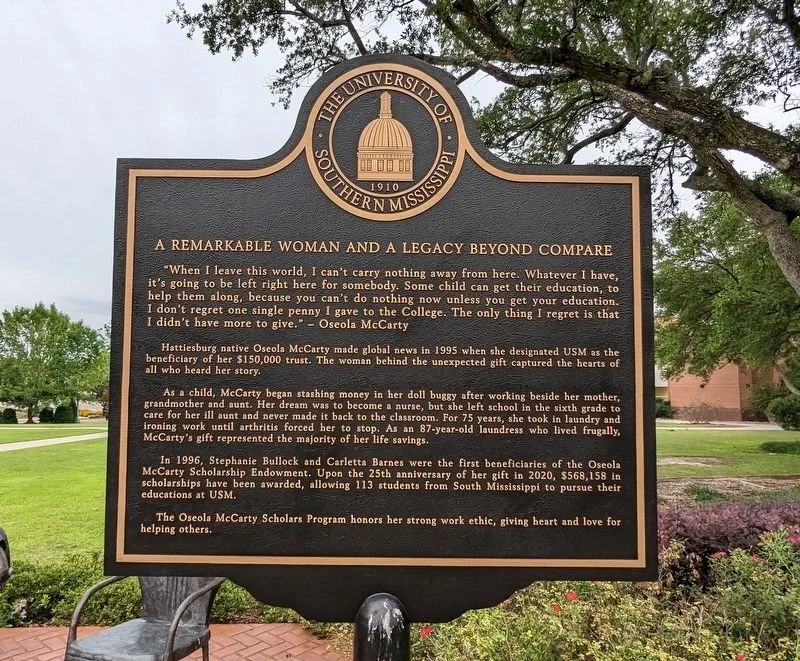

Bank managers soon reached out to help McCarty plan her estate. Decisions were made using dimes. With each coin representing 10 percent of her wealth, McCarthy set aside one dime for herself, and one each for three distant family members. She gave the rest — $150,000 — to the University of Southern Mississippi. School officials were stunned.

“No one approached her from the university; she approached us. She's seen the poverty, the young people who have struggled, who need an education. She is the most unselfish individual I have ever met."

Word soon spread. In the New York Times, Rick Bragg told the tale: “Oseola McCarty spent a lifetime making other people look nice. Day after day, for most of her 87 years, she took in bundles of dirty clothes and made them clean and neat for parties she never attended, weddings to which she was never invited, graduations she never saw. . .”

McCarty soon enjoyed a celebrity she never understood. She was flown to New York — her first plane ride — and put up in a hotel, another first. Before leaving the next morning, she made the bed. At the White House, Bill Clinton gave her the Presidential Citizens Medal. Harvard gave her an honorary doctorate. But she was more proud of the giving she inspired with what Hattiesburg called simply “The Gift.”

Ted Turner donated a billion dollars to various charities. “If that little woman can give away everything she has,” Turner said, “then I can give a billion.” Others gave to USM, tripling “The Gift.” And Stephanie Bullock adopted McCarty as her grandmother, driving her around town on errands. “She was just so sweet and so giving that you couldn't help but give her a big old hug every time you saw her.”

In making her gift, McCarty asked for no building, no statue, no endowed chair. She simply wanted to see the first recipient graduate. And in June 1999, Stephanie Bullock graduated, with Osceola McCarty watching. That fall, when Bullock had started on her M.B.A., McCarty died at age 91.

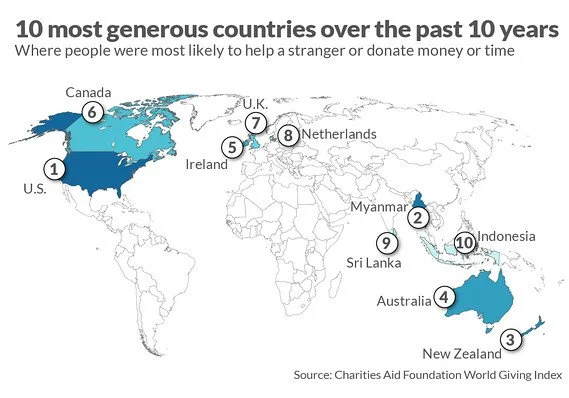

A remarkable story, yet it is not as unusual as America the Greedy would have you believe. “There are Oseolas all across the U.S.,” Philanthropy Roundtable noted, citing a half-dozen ordinary Americans who each gave away millions. Rather than being uniquely greedy, the Roundtable noted, Americans are uniquely generous.

“Between 70 and 90 percent of U.S. households make charitable contributions every year, with the average household contribution being about $2,500. That is two to 20 times as much generosity as in equivalent Western European nations. In addition, half of all U.S. adults volunteer their time to charitable activities, totaling an estimated 20 billion hours per year.”

Yes, we have our foundations — Ford, Carnegie, Rockefeller — yet of the $373 billion Americans donate every year, 80 percent comes from individuals. Few can match Osceola McCarty, yet The Gifts, large or small, carry her spirit.

“When I leave this world, I can’t take nothing away from here. Whatever I have, it’s going to be left right here for somebody. Some child can get their education, to help them along. I don’t regret one single penny I gave to the college. My only regret is that I didn’t have more to give.”

SHARE THIS STORY!