THE SAY-HEY KID AND "THE CATCH"

POLO GROUNDS, SEPTEMBER 29, 1954 — Experts agree that hitting a baseball — a round ball meeting a round bat squarely — is the toughest task in sports. Catching a baseball, however, is fairly easy. Little Leaguers make diving catches. Major leaguers catch 99 percent of everything hit their way. There is, however, only one catch called “The Catch.”

1954 World Series, Game One. Eighth inning. Two on, nobody out. Score tied 2-2. Cleveland slugger Vic Wertz has already tripled home Cleveland’s two runs. Now he faces a fresh relief pitcher. Don Liddle throws Ball One, Ball Two. The Giants’ centerfielder moves in a step. Liddle goes into the stretch. . .

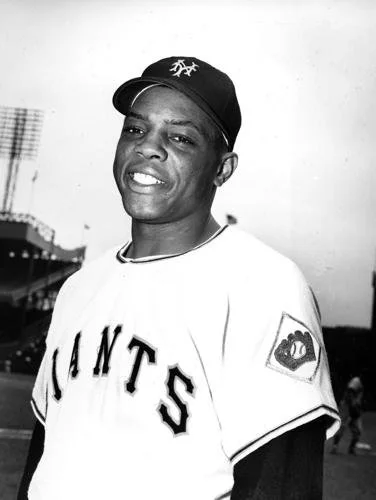

As one early biography said, Willie Mays seemed “born to play ball.” His father played semi-pro. His mother starred in basketball and track. At age 17, a year after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color line, Mays was signed to the Negro Leagues. After two seasons with his hometown Birmingham Barons, he joined the Giants’ farm system. Playing in Minneapolis, he was batting .477 when called to the majors. There his spirit rang out as loudly as his bat.

Unable to keep up with the crowd of new names, the 20-year-old greeted everyone with, “Say hey!”

“He had an open manner, friendly, vivacious, irrepressible,” one sportswriter recalled. “He projected a feeling that playing ball, for its own sake, was the most wonderful thing in the world.” But Joe DiMaggio said it best. “Willie Mays is the closest to being perfect I’ve ever seen.”

Liddle throws. . . Wertz tries to bunt the runners over. The ball goes foul. Mays takes another step in.

He missed most of ‘52 and ‘53 while serving in the army. Then in 1954, he bloomed. 41 homers. .345 average. National League MVP. And that glove.

One afternoon in Pittsburgh, Mays raced into deep center field. With the ball slicing away, he couldn’t reach across with his glove, so he stretched out and caught it with his bare hand. And one afternoon in Ebbets Field. . .

But this was the Polo Grounds, a “bathtub” shaped park. Foul lines ran just 280 feet, easily the majors’ shortest. Walls then balooned into centerfield, reaching 480 feet. Playing center in the Polo Grounds was like playing center in the Grand Canyon. Willie Mays was about to show how it was done.

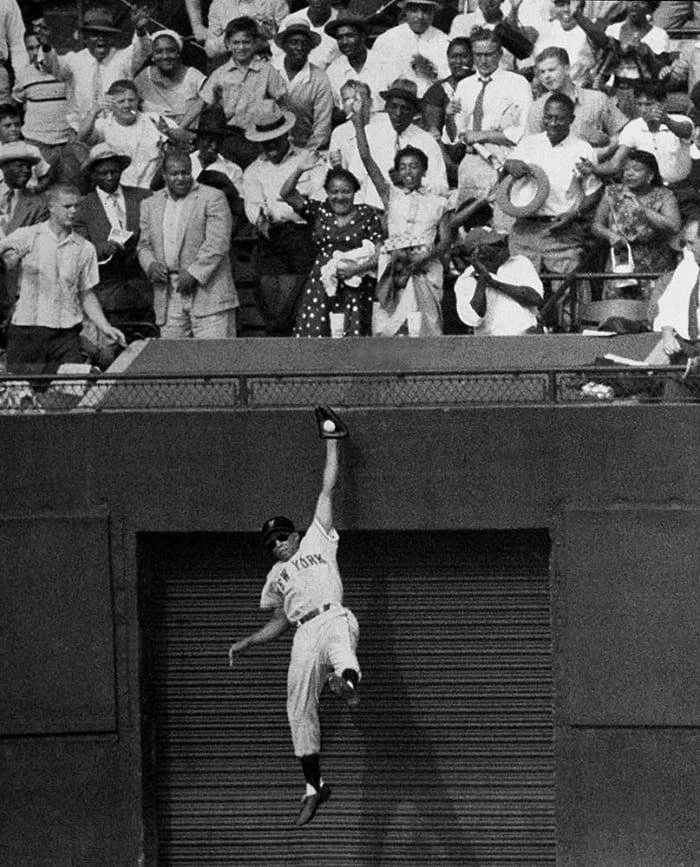

Two-and-one count. Liddle delivers. Wertz swings. “The hardest ball I ever hit in my life.” As the shot soars, Mays takes off, running some 30 yards in four seconds. A baseball is easy to catch — if you can catch up with it.

“When Wertz hit the ball,” one Giant said, “I knew if it was in the park Willie was going to catch it. He caught everything else.”

Mays also knew he had it all along. "Wertz hits it,” he recalled. “A solid sound. I learned a lot from the sound of the ball on the bat. Always did. I could tell from the sound whether to come in or go back. This time I'm going back, a long way back, but there is no doubt in my mind. I am going to catch this ball.”

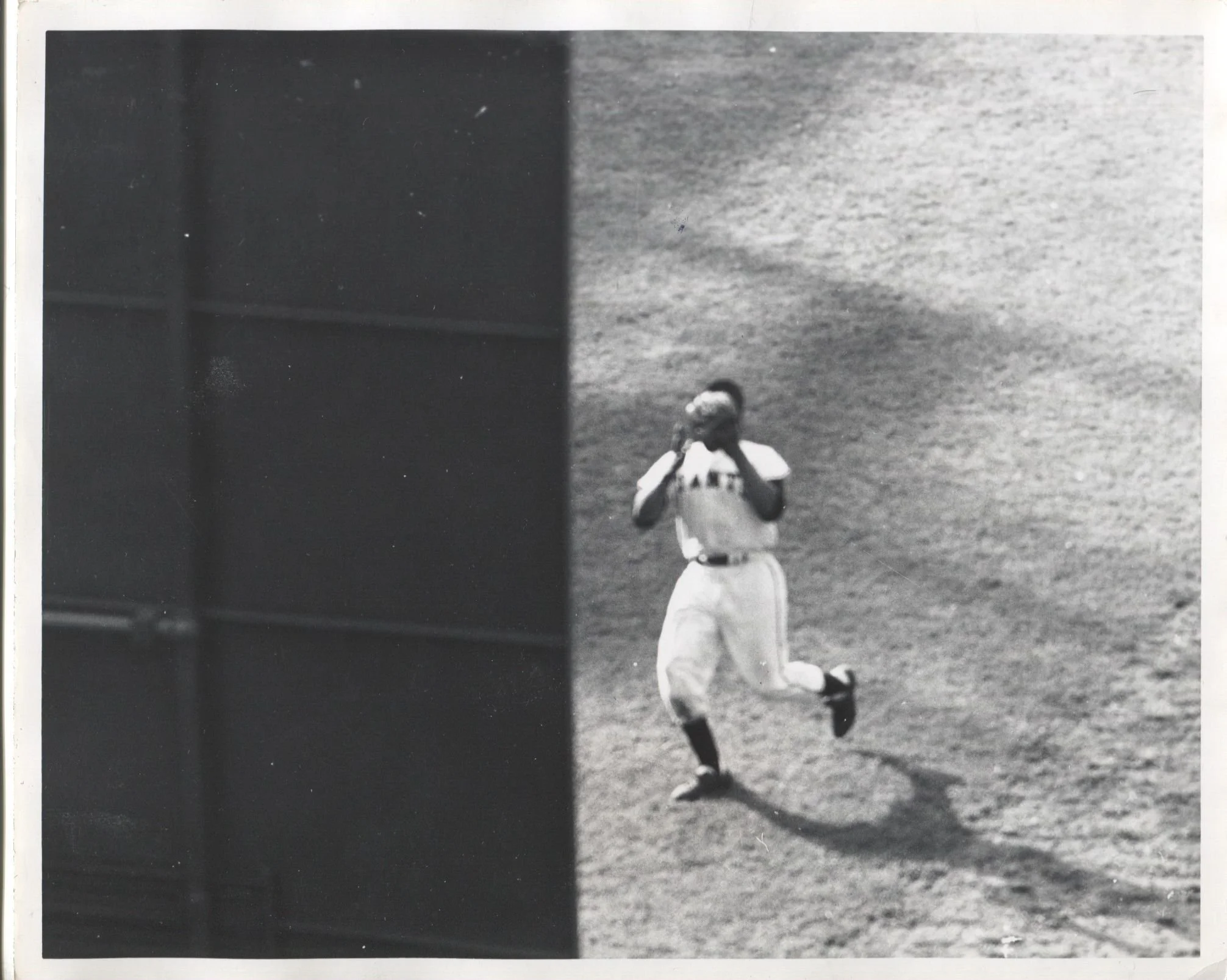

But the catch wasn't the problem. The problem was the runner on second base.

“On a deep fly to centerfield at the Polo Grounds, a runner could score all the way from second,” Mays said. “So if I make the catch, which I will, and Larry scores from second. . . All the time I'm running back, I'm thinking, 'Willie, you've got to get this ball back into the infield.'"

Sprinting with his back to the plate, Mays seemed to outrun the ball. At the last second he — oh, just watch. . .

Though it’s now known as “The Catch,” many still stand in awe of “The Throw.” Mays was actually braking as he caught the ball, fighting momentum to get something on the throw. And the throw hit cutoff man in short center, holding Larry Doby to third and keeping the runner on first.

Pitcher Don Liddle, taken out for another reliever, entered the dugout. “Well,” he said, “I got my man.”

Cleveland won 111 games that season, still a league record, but the Giants won that first game and swept the series. “Losing the first game hurt us the most,” their manager said. “Willie Mays made that great catch on Wertz' drive and we were never the same."

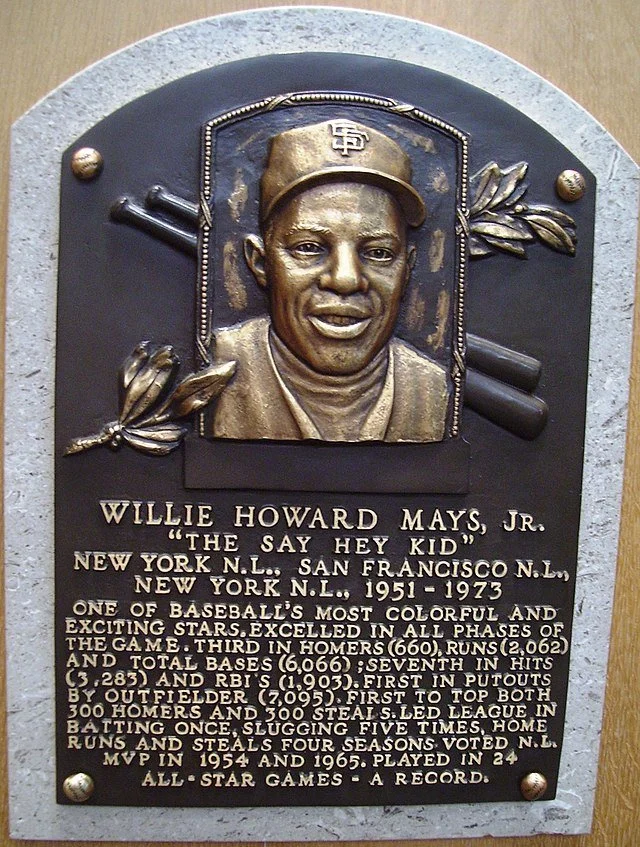

Mays, of course, went on to all-time greatness. 660 homeruns, 3,000+ hits, more catches in centerfield than anyone else — ever. Fans who saw him play never forgot him. (I was one.) But one fan got even closer.

The year after “the catch,” pitcher Don Liddle’s son visited the Giants dugout. Mays heard that the kid needed a glove to play Little League. “He gave me a glove,” Craig Liddle recalled, “and said it was the one he used in 1954 and part of 1955, and because he had broken in a new glove and was finally comfortable with it, I could have the old one.”

“You take care of it,” Mays told the kid, “and it will take care of you.” After playing two seasons with the glove that made “The Catch,” Craig Liddle kept it in a closet. In 1992, he gave it to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Last June, at 93, Willie Mays passed away. Tributes flowed, along with endless replays of “the catch.” But along with that split-second moment, people remembered what the “Say Hey Kid” meant to them and to America.

“Willie Mays,” the New York Times wrote, was “a name that even people far afield from the baseball world recognized instantly as a national treasure.” Writing to the paper, a fan added: “Farewell, Willie Mays. You thrilled and inspired an entire generation of New York baseball fans, and we are not likely to see anyone else play the game the way you played it.“